The archaeologist, the muse and the priestess

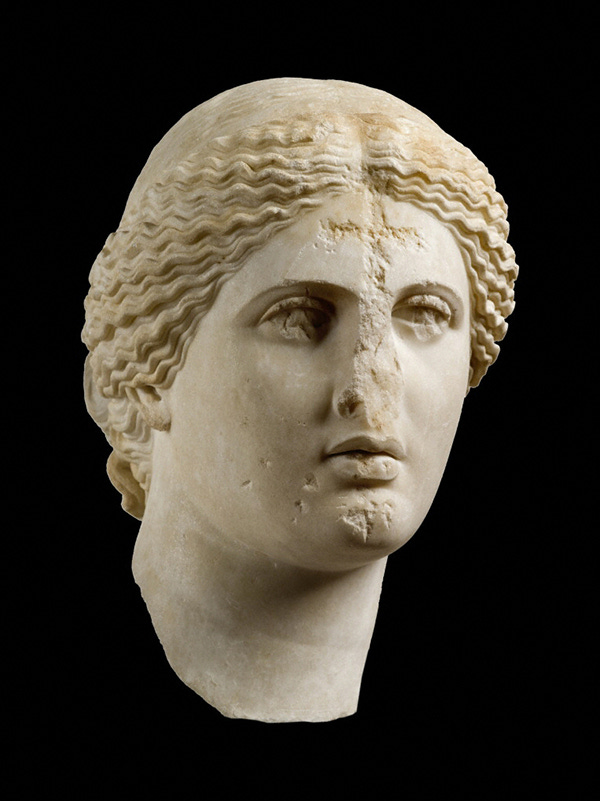

A goddess in 360°: stories from the Knidian Aphrodite

In the midst thereof sits the goddess – she's a most beautiful statue of Parian marble – arrogantly smiling a little as a grin parts her lips. Draped by no garment, all her beauty is uncovered and revealed, except insofar as she unobtrusively uses one hand to hide her private parts. So great was the power of the craftsman's art that the hard unyielding marble did justice to every limb.

(Amores, attributed to Lucian)

The Knidia, or the Knidian Aphrodite, is the most famous iteration of this goddess of passionate love and desire. She is often described as standing “suggestively”, making a half-hearted attempt to conceal her genitals as her towel drops carelessly behind her. The gentle contrapposto of her body draws the eye along the curvature of her body which simultaneously stands slackened and firm with life.

Much has been written about her. Pliny the elder wrote in his Natural History how the shrine on the island of Knidos that housed her was open so ‘the goddess could be seen from all sides’. She was made with ‘the goddess’s approval’ to be ‘admired from every angle’. Bringing the ick factor is the tale of the ‘man who had fallen in love with the statue’ who ‘hid in the temple at night and embraced it intimately. A stain bears witness to his lust.’

Scholarship has traditionally (predictably) argued that the Knidia was made for the male gaze, although, in the last decade, it’s been suggested that women were indeed her intended audience.

Whoever the intended audience, the Knidia is widely believed to be the first female take on the Greek heroic nude. In her book Venus and Aphrodite (History of a Goddess) Bettany Hughes writes: ‘A trend had been fuelled. Aphrodite-Venus would find it very difficult to keep her clothes on, and command serious respect.’

Indeed, nude variations on Aphrodite (mostly inspired by the Knidia) became hugely popular throughout antiquity and beyond.

I’d like to pause to think about a few women (two real, one imagined) who are inextricably linked to this statue (and its story), which, immortalised in flames and imprinted through iteration, has become myth itself.

Much has been written, despite the fact that no living person has ever seen the original sculpture.

Here’s what we know:

The island of Knidos bought this nude goddess from the famous sculpture, Praxiteles.

She was likely sculpted between 360 - 330 BC.

She had a clothed counterpart, which was purchased by the neighbouring island of Kos.

The original Knidia – the one you’ve never seen – was destroyed in a fire in Byzantium at the Palace of Lausus. All we have today are the aforementioned copies.

This isn’t intended to be an academic investigation into the Knidian Aphrodite’s conception or reception (I’ll leave that to the proper scholars). Rather, I’d like to pause to think about three women (two real, one imagined) who are inextricably linked to this statue (and its story), which, immortalised in flames and imprinted through iteration, has become myth itself.

Iris Love: the archaeologist

How could I not include the deliciously (and aptly) named Iris Love? She deserves, I think, a post to herself (this to come)! On the same summer day in 1969 that Neil Armstrong walked the moon, Iris Love discovered a temple to Aphrodite in Knidos. This would become an eleven year dig.

Once known as ‘the archaeologist in a mini-skirt’, she directed the all-female crew in The British Museum’s store rooms after identifying what she believed was a lost head fragment from the Knidia. At the time, archaeology was awash with sexism…and a distinct lack of imagination. She was derided by the institution – misunderstood by her aesthetics and appearance (on top of the mini-skirt epithet, she received many comments about her facial creams and “overtly” female presentation). Her goddess Aphrodite would surely relate to such scrutiny.

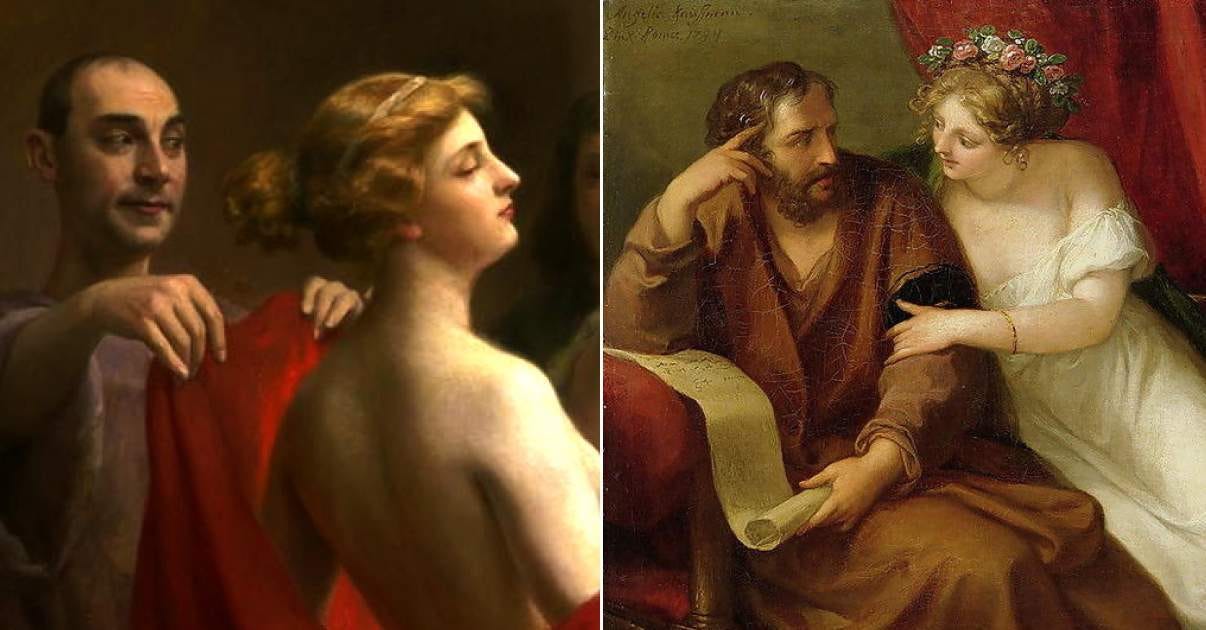

Phryne: the muse

Perhaps most famed for her trial in Athens for ‘impiety”, this 4th century BC courtesan was one of the most successful in Greece. Praxiteles, the Knidia’s sculptor, was a client. It’s widely believed that Phryne posed for him in the creation of the original sculpture. Acting as a muse for art works was commonplace for ancient courtesans.

For me, this gives the Knidia a new dimension: we are not just viewing a goddess at play, we are viewing a woman. And a woman who commands men expertly enough to elicit great fortune and fame.

Cilissa: the priestess

Aphrodite was not always the nude ideal we see in our mind’s eye. At around 1300BC, Early Greek travellers (driven by drought) arrived at Cyprus. The conflation of culture saw a conflation of a goddess at the sanctuary at Paphos: a Cypriot nature deity, an Eastern goddess of war and love (Ishtar) and Greek ideas surrounding a goddess to do with fertility and relationships.* She is terrifying, burgeoning, not yet formalised as the Classical Aphrodite-ideal she will become.

Based on research, I have indulged myself (because, why not?) and imagined one of her early priestesses (around 900BC) at the sanctuary at Paphos. I have named her Cilissa:

A thing spits in the corner of the temple. Cilissa gropes with her eyes, which sting with incense, through the torch-fingered shadows. The lotus fumes have thickened her senses.

She is sure she heard it, though.

A wet and seething sound. One that reminds her of ointment on a flame. It is impatient. It is hungry for air.

It spits again and, this time, a seething, rattled breath reaches the short distance from the inky dark, landing on her damp lips. Cilissa tastes oil and salt and blood and wine. She swallows, ignoring the prickly tension which has formed at the base of her skull. She is grateful for these hallucinations. They bring her closer to the Cypriot. She remains nestled on the floor.

The sacrificial flame burns at the bottom of the steps outside. Its orange, flickering fingers reach beneath the doors. She listens to her sisters rearranging the baskets for tomorrow’s offerings. They whisper, barely audible, but she knows what they say: who wants the spares of bread? Lots today. Come, that corn is wilting. It must be refreshed for the goddess. She detests decay, as we know.

As is often the case after an afternoon of wine, she infers she must have fallen asleep. She hangs her head between her knees, happy she’s been allowed to rest, yet troubled by being left behind. She realises there is little lonelier than waking before dawn, the gritty residue of leather wine sack at the back of your throat, to the sound of companions who have continued without you.

Cilissa presses her feet against the cool slabs, readying to stand. She is unsteady, her bones are fluid and warm, but she wants to join in. After the sanctuary is tidied, they will guard the fire in a tight circle and inhale the florid fumes.

Then they will recite incantations.

At the first sign of morning, they will walk the narrow path down the foothill. The dusty road will give way to sand and rocks, where they will strip before submerging themselves in the lagoon. Floating on their backs, they will blink at the sky as Helios turns it first purple, then pink, then yellow before the blue breaks through. The water will do her good, she thinks. Salt has sharpening properties.

A gurgle, almost like a foaming whirlpool in the sea, commands her attention. She smells burning – it hovers between acrid and sweet. Her insides uncoil, tautened and attentive like the scales of a threatened snake. She stands, her fists pressed against her thighs. If she makes for the heavy doors, she will turn her back on the unknown. She won’t move fast enough to reach her sisters if the thing is dangerous. Two thoughts occur to her: how long has she been watched whilst sleeping? Why have her sisters shut the doors?

‘Who is there?’ Cilissa has never liked her voice. She has always been jealous of the others who have cultivated a lower, chesty register. Their songs and recitals command more respect than she does. Here, her thready, sparrow-like tone mocks her.

She squints, raising her hands before her as if she can peel away the darkness. She focuses on the spot from which the sound came. Just before the entrance to the opisthodomos, there is a bundle. Some rags, or other discarded cloth. Apart from the bundle moves. It shivers. It is, she is sure, organic matter.

The remnants of tannins clump at the back of her throat. Her chest constricts. Cilissa breathes to scream for her sisters but the thing moves so quickly that her mouth is snapped shut by the air churning about it.

‘Do not.’

It is not a voice. She hears the words but they are too porous. They are impossibly magnified yet at the same time painfully intimate. She realises her eyes are clenched tightly closed yet something stews before her. Sodden lungs contract and release; liquid bubbles and sputters. A weight of inevitability presses down on her shoulders. Her eyes open. She is face to face with it.

The thing is terrible, but not ugly. Cilissa has never looked at anything before and felt her whole body curdle at the sight. What an awful sensation it is to be drawn to something so intensely, yet feel fear tremble behind the sinews of her knees.

*Bettany Hughes, Venus and Aphrodite